Before the Law: The Scales of Justice and the Weight of Power

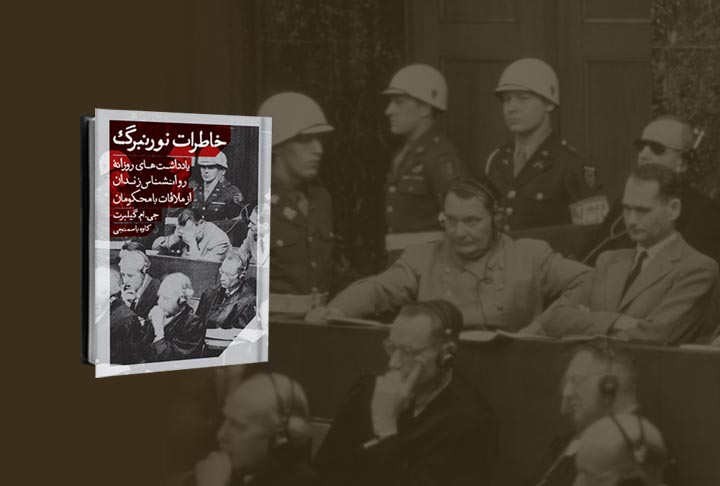

By: Kaveh Basmenji (A summary of the foreword to the Persian edition of Nuremberg Diaries by G. M. Gilbert)

In 2011, a decade after al-Qaeda’s deadly attack on New York’s Twin Towers, U.S. President Barack Obama decided that the suspects—who had been held for nearly ten years in Guantánamo Bay—would be tried not in civilian court, but before a military tribunal. The justices of the U.S. Supreme Court had failed to reach a unified position on the matter. Obama’s decision sparked a major controversy in the United States. Many American intellectuals—especially those on the left—feared that a military trial would turn the defendants into martyrs or heroes. Obama, who had campaigned on a promise to close Guantánamo, fell from grace in the eyes of many of his supporters.

At the time, the prominent American journalist William Shawcross defended Obama’s decision in The New York Times, arguing that a military court did not necessarily mean an unjust one. He cited the Nuremberg Trials as an example: “At Nuremberg,” he wrote, “our civilization created a channel through which it could express its revulsion at men consumed by hatred. Nuremberg is a precedent America can be proud to stand on.”

Years earlier, the debate over punishing terrorists had been just as fierce. The British writer George Orwell, renowned for his moral courage and political honesty, made a startling remark in late 1943 as World War II began turning in favor of the Allies: he argued that after the war, Hitler and Mussolini should be left alone—that their punishment should not be death, unless Germans and Italians themselves executed them without trial. (Indeed, Mussolini ultimately met that fate.)

Orwell feared that, like Napoleon, those dictators might later be mythologized—or turned into “martyrs.” Above all, he despised the idea of a hypocritical, theatrical trial for war criminals, believing that such pageantry “inevitably casts a romantic light on the accused over time and turns a murderer into a hero.”

Contrary to Orwell’s fears, the trials went ahead—and contrary to his prediction, neither Hitler nor Mussolini became heroes or martyrs in the eyes of the world. Their ideas, however—nationalism, racial superiority, propaganda, and what we now call populism—have reappeared in new forms. The twenty-first century has seen a resurgence of nationalism, white supremacy, xenophobia, fake news, and the rise of populist leaders from Europe to the United States, Russia to Latin America.

On April 20, 1942, representatives of nine nations occupied by Germany met in London to draft the Allied Resolution on German War Crimes. The three major powers—Britain, the United States, and the Soviet Union—agreed on the framework for prosecuting Nazi war criminals at the conferences of Tehran (1943), Yalta (1945), and Potsdam (1945). France was also granted a role in the tribunal. The legal foundation was the London Charter of the International Military Tribunal, limiting jurisdiction to “major war criminals of the European Axis.”

Yet this consensus was hard-won. Ultimately, about 200 senior Nazi officials were prosecuted at Nuremberg. The tribunal’s legal authority rested on Germany’s act of surrender.

The American historian Joseph E. Persico described Nuremberg as “a beautiful idea murdered by a gang of ugly facts.” His argument was that the trials’ noble intentions were undermined by the messy realities of implementation. But justice, unlike science, is subjective—fraught with human error. Nuremberg cannot be painted in black and white: wholly successful or failed, fair or unfair.

Decades later, most Western scholars came to view Nuremberg as the only viable choice for the victorious Allies. But at the time, it was anything but obvious how to deal with the Nazi leadership. In A Hand of Vengeance: The Politics of War Crimes Tribunals, Gary Jonathan Bass notes that many Allied leaders favored summary executions. Winston Churchill and Franklin D. Roosevelt, following Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau’s advice, supported swift executions for top Nazis. British cabinet papers declassified in 2006 reveal that Churchill even sought to use a “summary execution law” to bypass legal hurdles—before being dissuaded by Roosevelt.

The Soviets, by contrast, preferred rapid show trials followed by mass executions. Allied public opinion overwhelmingly supported the death penalty: only about 10 percent favored trials—roughly the same percentage who wanted the Nazis slowly tortured. At the Tehran Conference in late 1943, Joseph Stalin suggested executing 50,000 to 100,000 German officers. Roosevelt joked that perhaps “49,000” would be enough. Churchill objected, saying he’d rather be shot himself than “execute soldiers who fought for their country.” Eventually, the Western powers prevailed.

One main argument for summary executions, as Persico observed, was that “honest vengeance is better than endless legal wrangling.” This implied criticism of law itself: war, being political, should have political—not legal—solutions. The Dutch journalist Ian Buruma asked in The Wages of Guilt: “Why bring the law into it? Why not make a political decision and punish them?”

Many believed, as Hermann Göring put it, that any trial would be “the justice of the victors: the victor is always the judge, and the vanquished always the accused.” Even some Allied jurists agreed. U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice Harlan Fiske Stone called Nuremberg “a high-grade lynching party.” Another writer said it was “a political act serving political ends, decided by political leaders.”

The Soviets, steeped in Stalinist legal culture, saw no problem with show trials: for them, trials were instruments of propaganda, and guilt was presumed. A week before Nuremberg began, Soviet Deputy Foreign Minister Andrei Vyshinsky famously declared: “May their path lead straight from the courtroom to the grave.” The Soviets were furious when three defendants were acquitted and seven others spared the death penalty—a stark contrast between liberal and totalitarian notions of justice.

In Central and Eastern Europe, the tradition was similar. As Milan Kundera wrote, in the Kafkaesque sense, the “Court” is powerful precisely because it judges; its authority alone grants legitimacy. “The trial is not held to deliver justice—it exists to destroy the accused.”

Six decades later, views on Nuremberg remain divided. The enormity and cruelty of Nazi crimes were so staggering that few—at least publicly—doubt the guilt of the accused. Yet critics have long challenged Nuremberg on three main grounds.

First, they question its legality: that the tribunal retroactively created laws (ex post facto). While few doubt the defendants’ guilt, many criticized the judicial process. An American jurist wrote at the time, “Justice is only served when guilt is determined carefully, conscientiously, under existing law, and by a legally appointed judge.” Even Justice William O. Douglas of the U.S. Supreme Court later said the Allies had “substituted power for principle,” writing, “I thought then, and still think, that Nuremberg lacked legal principles. Law was written after the fact to fit the passions of the time.”

Second, critics argue Nuremberg was “the law of the victors.” What right did the Allies have to stage military trials of another nation’s leaders? They pointed out the Allies’ own record of war crimes—from Britain’s colonial atrocities to the indiscriminate bombing of German cities. U.S. prosecutor Robert Jackson himself admitted in 1945 that the Allies were committing acts similar to those for which they were prosecuting the Germans.

Third, thinkers such as Hannah Arendt believed Nazi crimes were so unprecedented that no court could adequately judge them. “The purpose of a trial is only to render justice,” she wrote in Eichmann in Jerusalem, “but the law has no adequate tools for dealing with radical evil.”

The architects of Nuremberg insisted they were testing whether law itself could stand against barbarism. As Lawrence Douglas later wrote, the tribunal aimed to prove that “the power of law, by its dispassionate authority, could punish even the most monstrous crimes.”

Practically, the tribunal also reflected liberal Anglo-American “concerns for due process.” Leaving justice to the Germans was unthinkable: the failure of post–World War I trials had helped fuel Nazism’s rise. Some scholars thus argue the four Allied powers were justified in sharing German sovereignty to restore justice.

The most enduring legacy of Nuremberg was legal: the Nuremberg Principles, drafted by the U.N.’s International Law Commission. They established that individuals—not states—bear responsibility for war crimes, and that “following orders” is no defense. These principles later inspired the creation of the International Criminal Court in The Hague, which tried war crimes in Yugoslavia and Rwanda—though the United States itself has never joined.

Western critics, however, still accuse their governments of hypocrisy and double standards: justice for others, impunity for themselves. In 1966, philosopher Bertrand Russell organized a symbolic “tribunal” in Stockholm to investigate U.S. actions in Vietnam, with judges including Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir. Their verdict: guilty.

In 1990, Noam Chomsky wrote that if the Nuremberg Principles truly applied, every U.S. president since World War II—“perhaps except Jimmy Carter”—would have been hanged for the same crimes. Thirty years later, four Blackwater contractors convicted of massacring civilians in Baghdad’s Nisour Square in 2007 were pardoned; yet the very fact that an American court had convicted Americans for crimes abroad was, in itself, telling.

The idealized image of Lady Justice, blindfolded with scales and sword, is far from reality. Wealth, power, and politics always try to tip the scales. Yet in the West, the media remain free to expose abuses, and courts—however imperfect—still operate within constraints of accountability. It was the press that exposed Vietnam, Abu Ghraib, and Bagram; even the vast machinery of U.S. power could not silence them.

And still, more than seventy years after Nuremberg, the timeless questions remain: What is the relationship between law and justice? Who has the right to write the law, to decide right from wrong, to determine human destiny? Can there ever be a perfect law? If not, is no law better—or flawed law?

In Raymond Chandler’s novel The Long Goodbye, one character says:

“The law isn’t justice. It’s just a machine, a badly imperfect one. If you press the right buttons—and you’re lucky—maybe you get justice. The law was never meant to be anything more than a machine.”